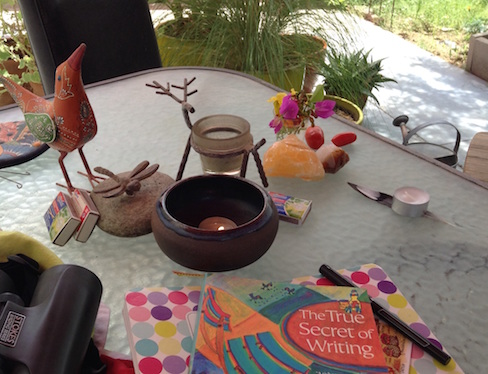

Today I finally build a small altar for my cat Sofia on the table in the courtyard. Tomorrow she will have been dead for one week, but I spent a good part of that time agonizing, torturing myself, replaying things over in my head. There was a lot of blood, too, on that last day. It took time for the shock to fade. So only today do I feel clean grief. It makes me grateful. I want to write about it. I have a lot to say. But I am vulnerable and exhausted and not ready. Still, I can’t say nothing. The first day or two after she died, I kept thinking I could smell her terrible cancer breath. (I wanted it to be true.) And there is that weird presence, that lit up place she used to fill, that keens her absence like a ghost. She is not lying under the bed. She is not in the closet. (The door is no longer ajar.) She should be here, but she’s not. “She’s never coming back,” I tell my boy cat. I think it’s sinking in. I still can’t walk into the back room without checking the floor to make sure I don’t step in pee. I want to go back in time and tolerate every annoying thing she ever did. I want to remember the clear look in her eyes on that last day when I slid the closet door open to say good morning. I want to kiss her soft furry head again and again and again. I feel like I have a whole book to say about her inside me. Here is the first snippet. Know you are loved, my darling girl. We miss you. Be well. Oh, please, be well.

[Photo courtesy of Marylou and Richard, shot the last time they tended my two little ones when I was away. Thank you.]