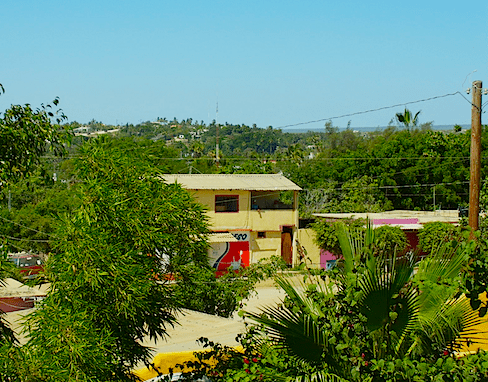

I’d pulled out the travel section of my L.A. Times a few weeks ago and set it aside unread. The cover story was about Mexico, about the northern village made famous for its pottery. Now the next generation are doing marvelous contemporary things with clay, and I’ve saved the photographs of big beautiful pots for my mother to see. There is one in particular I think she’ll enjoy that reminds me of some of her own large slab bowls. Nestled between the images of the pottery is a shot of one side of a village street, and I am transported. It could be any rural village in Mexico–the narrow, uneven sidewalk, the crumbling edges of things, the dirt road, the fading paint on the walls of the buildings. But what makes this so different from a dilapidated block in some U.S. town? Why does it awake a longing in me, a fondness, even, none of the aversion I might feel for the equivalent in this country? Is it the colors, the texture, the light? Is it the lack of despair in that Mexican air that weighs more lightly on the world? And why do I crave it?

When I moved back to the States, I remember my shock at the clean, wide streets, the lavish landscaping. Now I teeter between pleasure in the places where this wealth allows for a clean beauty, the brick and the desert plants and vivid blooms a masterpiece, often echoing our Spanish roots here in the Coachella Valley, and my dismay and disconnection from the places where the clean wealth falls short of this art and only looks garish and sterile, even obscene. But when I see this photograph of the village street in the newspaper, I ache to be there, walking along the banqueta, the sidewalk, my sandals dusty, my skin drinking in that other sunlight, the colors and the textures akin to the earth, to life, to participating in the world in a different way. I can’t quite grasp the words to explain it even to myself. It is a knowledge and a memory of the body, I think, and the spirit, not the mind.

I can feel myself nodding to two women I pass on the street. “Buenas tardes,” I say.

They take me in with their eyes, nod, smile. “Tardes,” they say.