When I lived in Ajijic, the lake flooded. It wasn’t the worst the village had lived through. People told me years before Lake Chapala came two blocks into town. The year I was there, she only swallowed the shoreline. But I remember the eery feeling I had seeing everything submerged. I used to be able to walk straight down Aldama from my hillside home, then walk along a dirt path that hugged the southern edge of the village beside the lake. All of that was submerged, even the cobblestones of my street disappearing into the water. I stood there for a long time listening to the lapping of the small waves, felt my mind twisting with the reality before it. I walked across town, approached the lake from the west.

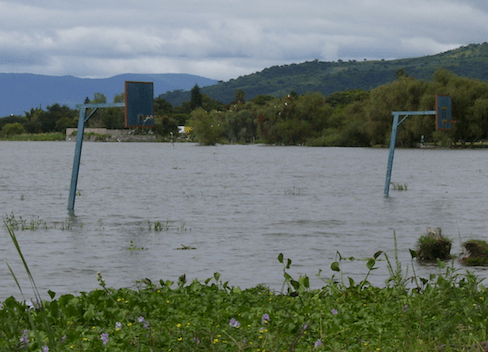

I marveled at the way the basketball courts had vanished, the hoops sitting out in the water. The lake edged the tennis courts at the fence line as if by design. I watched the egrets sitting on the chain link, their unexpected furniture. The little sign asking people not to bother the birds was still visible, the tree it was posted beside surrounded by lake. Two people passed me on horseback, the horses legs churning up the mud. I cringed at what their hooves might find, hoped they wouldn’t be injured. It all made me glad I lived on the hillside, as often as I might have looked at homes nearer the lake with a certain longing. On the hillside, the thunder gods sat on our red tile roofs and laughed. But when the rains came, the rivers of our streets ran away from us. I stood watching the horses heading east where I couldn’t follow. I choose thunder, I thought.